|

WorcesterThen: 1781-1821

|

|

The Changing Landscape of Worcester During the Federal Period Don Chamberlayne March, 2018 |

|

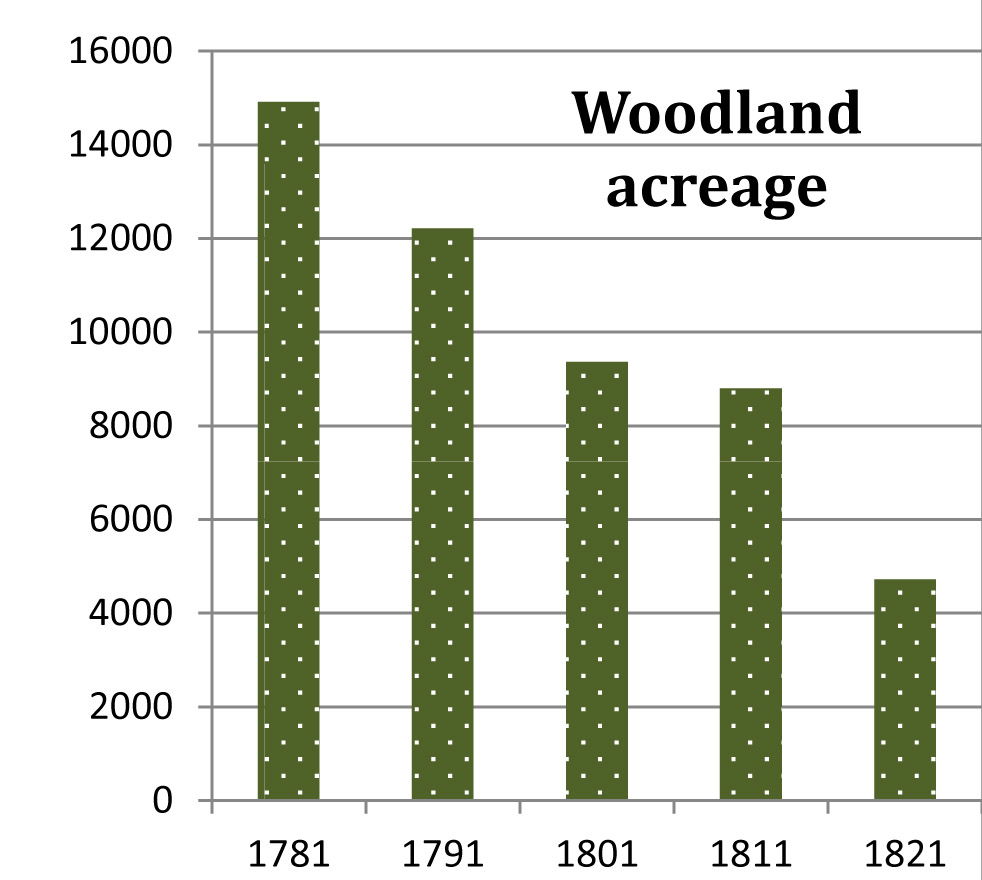

During the forty years between 1781 and 1821 Worcester lost over 10,000 acres, almost 16 square miles, of woodland and otherwise “unimproved” land. It was enough to change the town from nearly two-thirds wooded to barely one-fifth. Some necessary preliminaries: First, the source of the data. In his History of Worcester, first published in 1836, William Lincoln presented data on woodland and other uses of land, as well as other agricultural information, for each tenth year between 1781 through 1831, drawn from the state summaries of reports of local assessors, a procedure that had begun during the colonial era.* The book was published by Charles Hersey in 1836, then re-published in 1862, a quarter-century after Lincoln’s death, with an extention written by Hersey himself. The key page (p. 262) can be seen here. Second, data on woodland and unimproved land (not suitable for agricultural use) are combined because it was not until 1801 that they were separated. For present purposes there is no harm in viewing them in combined form for all five years. The combination will be referred to as “woodland.” Third, comparable data for 1771 are available, although from a different source, and have been discussed and interpreted in The Worcester of 1771. The reason for not including 1771 data here is that between 1771 and 1781 a change in town geography occurred which caused a significant discontinuity in the data, making inferences about changes in land use or any other agricultural factor unreliable. In 1778, approximately 3.5 square miles (2250 acres) of land in the southwest corner of the town was ceded to the new town of Ward, which later became Auburn. In addition, though the date is not known, some land was added to Worcester along the border of Millbury and Grafton. As a result of these changes, there is no way to know how many acres of woodland or any type of agricultural use were subject to the changes. |

|

|

The clearing of wooded acreage continued fairly consistently throughout the period, although there was a slowdown in the third decade, which was followed by a speed-up in the fourth, the 1810s. (Woodland acreage was not available for 1771.) The proportion of the town that was wooded (or “unimproved”) fell from about 65% in 1781 to about 21% in 1821. (Some, like the author, may find it a bit painful to think about the number and the size of the hardwoods in the old-growth forests -- now rare, expensive, sometimes endangered, and some all-but-extinct, such as the great chestnut.) Why did this happen? What explains this amount of land clearance? |

|

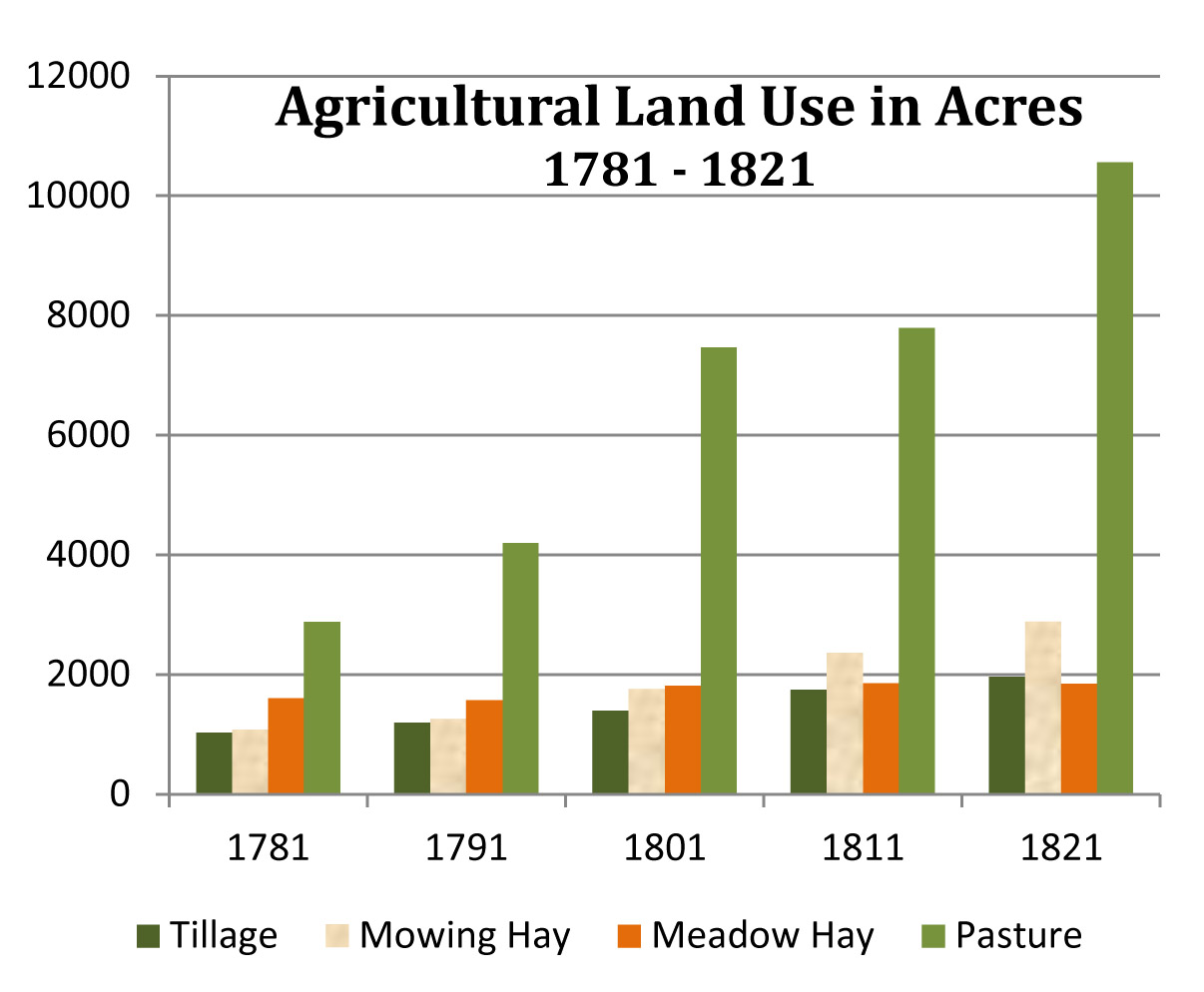

The most likely cause would be the growth of the town that occurred during that period. More people, families, and houses would require lumber for building and cordwood for heating and cooking. But was there enough such growth to explain the need for that much wood? Probably not. Population growth in Worcester during this time was slow to moderate, at best. From an estimated 1700 persons in 1771 (ignoring the loss of some to Auburn), the population increased to 2962 in 1820, according to the census of that year. That amounted to a very temperate gain of 74 percent in 49 years, the product of growing at an average rate of barely over one percent per year (three or four families, houses, etc. added each year). The wood required to support such a rate of growth could have been harvested in a manner consistent with conservation of the woodlands. Much more likely is that the great land clearance of the period was primarily a result of a need for more open land for agricultural purposes. Some increase in open land logically would follow from an increase in the number of farms, or in the average size of farms, or both. To get a sense of scale, the number of acres of land in agricultural use per house in 1781 was 30.5 (6595 acres, 216 houses). In 1821 it was 44.9 (17,248 acres, 384 houses). An increase of 50% in agricultural use of land over a 40-year period does not seem surprising. Whether all that land was actually in use is another question. Some landowners may simply have wanted to “improve” their land by clearing all or most of the trees on a portion of it, rendering it usable for agricultural purposes in the future, even if such land was not immediately needed. To the extent that trees were cut to increase land suitable for agricultural use, the question arises as to what they did with the trees, beyond the amount needed for lumber, fuel, fencing, etc. Steam power hadn’t arrived yet, and the export of timber was severely constrained by the fact that the town was severely landlocked, with no navigable rivers. More likely, a considerable amount of the excess of felled trees was burned and the ashes used to make potash for export. Data on the various uses of land in farming during the forty-year period were included in the assessors’ survey presented by Lincoln. As seen in the graphic below, they consisted of tillage, two kinds of hay, and pasture land. (For more on this subject see The Worcester of 1771.) |

|

|

Agricultural uses of land expanded over the 40-year span by 10,563 acres, a bit over 16 square miles, and roughly the same as the loss of woodland and unimproved land, as would be expected.* The increase amounted to 162%, compared with a 78% increase in houses and families. * The increase in agricultural acreage was slightly larger than the loss of woodland. The reason for this anomaly is unknown, but the difference is less than four percent. Acreage in tillage nearly doubled, and land used for hay increased by a bit less, but the largest gain by far was in pasture land, as it accounted for 72 of every 100 new acres brought into play by the clear-cutting of woodlands. |

|

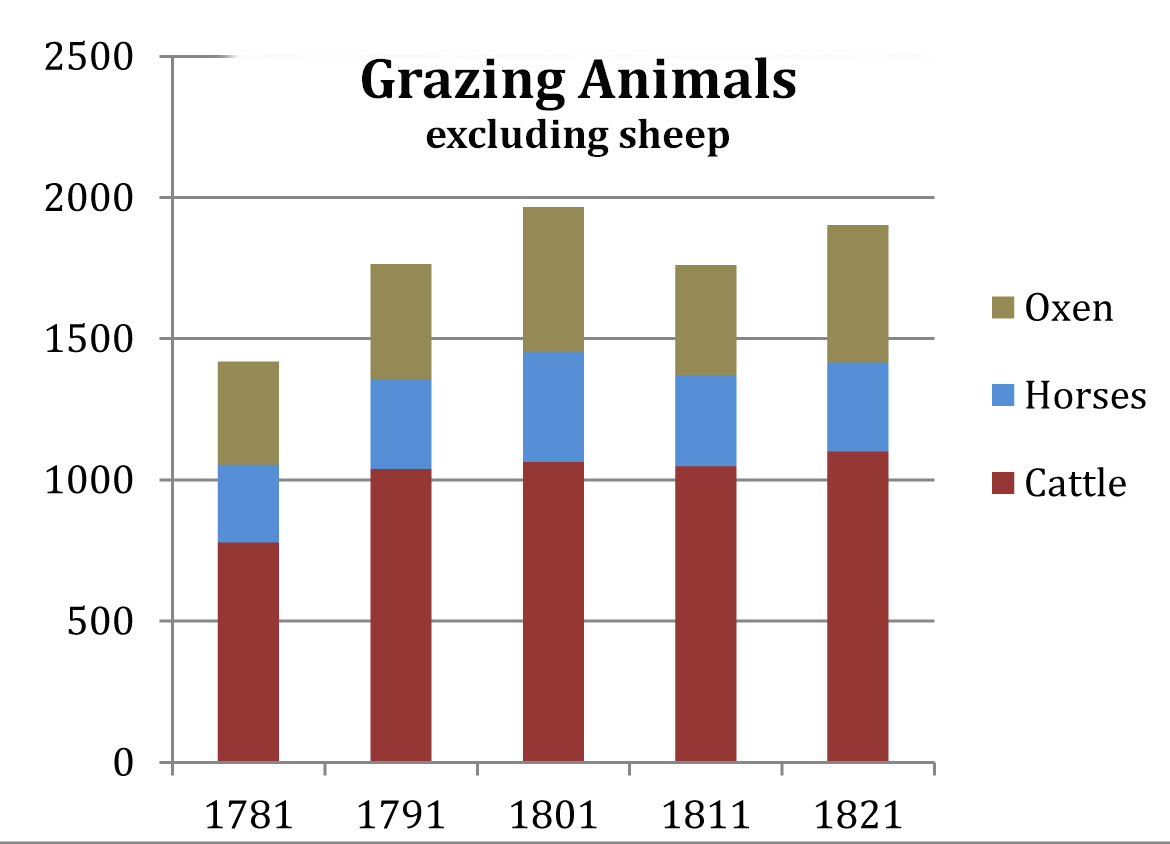

It is unclear to what extent this increase in pasture land was a cause of the clearing of so much woodland, or a result of it -- a product of the newly-cleared land being classified as pasture by default, because it was not in use for tillage or hay. If the latter is true, which is certainly possible, then the question of why they cut down so much timber is still open. In other words, if there was not enough need for pasture land to justify so much clearance, then why did they do it? A reasonable assumption would be that the purpose of the expansion of pasture land was to accommodate an increase in the population of grazing animals. Data on grazing animals were also provided by William Lincoln, based on the same local assessors’ reports. Unfortunately, however, and for reason unknown, he did not include data on sheep or goats. That fact obviously makes the task here more difficult, and it limits any conclusions to speculation. |

|

|

Excluding sheep and goats, the number of grazing animals increased by only 483, a gain of 34%, over the 40-year span, the largest share of the increase attributable to cattle. Thus, increase in grazing animals failed by far to keep pace with the increase in pasture land. With nearly 7700 new acres of pasture coming into service, the net result was about one additional animal to every 16 new acres. The grazing density -- animals per acre of pasture, excluding sheep -- fell from 0.49 in 1781 to 0.18 in 1821. That would have meant a large quantity of under-utilized pasture land. |

|

That leaves the sheep to be considered, which is difficult because of the lack of data. Fortunately, however, in 1771, the assessors’ survey did report numbers of sheep and goats. Despite the matter of the ceding of land to Auburn and the smaller gains from Millbury and Grafton, it is helpful to consider the available data on sheep and goats in 1771. The fact that the two animals were combined in the counts is a mild annoyance, although the problem can be bypassed, assuming that most of any significant gain over the years would be in sheep. Provided there was an adequate market, more sheep would mean more sales of wool for cash that could be used to buy goods elsewhere, while goats, being used mainly for milk, cheese, and keeping the grass under control, were more likely just to increase with the number of family farms. (Hereafter, “sheep” means “sheep and goats combined.”) In 1771, the grazing density excluding sheep was 0.8 –- eight animals per ten acres. The number of sheep counted that year was 1,512, which was slightly more than the other three grazing animals combined, so including them raises the grazing density to 1.6 (3,016 animals on 1,888 acres). |

|

These facts make it possible to determine how many sheep it would have taken each subsequent decennial year to maintain such a grazing density, or to maintain any hypothetical grazing density. The formula: The number of acres times the grazing density yields the total number of animals, from which is subtracted the number of other animals, leaving the number of sheep required. For example, in 1781, a grazing density of 1.5 applied to 2,881 acres of pasture yielded 4,322 “spaces” for animals. Subtracting the 1,420 other animals leaves space for 2,902 sheep.

The results: Numbers of sheep required to maintain selected hypothetical grazing densities: |

|

At a grazing density of 1.5, slightly below that found in 1771, the number of sheep would have grown to nearly 14,000 by 1821, a gain of more than 11,000 in forty years –- 480%. In this case, sheep would have made up 88% of all grazing animals. A lower assumed grazing density makes the numbers smaller, of course, but even at 1.0, just one animal per acre, the number of sheep would have been over 8,600 in 1821. That would have meant 82% of the animals in the fields instead of 88%. That’s still a lot of sheep. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The lower the assumed grazing density, the fewer the sheep and the greater the reason to ask why the woodlands were cleared at such a rate. It is possible, but not a conclusion supported by facts, that during the period between Independence and the onset of the industrial age, the Federal period, Worcester became a town of considerable sheep-husbandry. If this hypothesis is true, farmers likely were responding to an enhanced market for wool to supply the growing number of woolen mills in the region. It would have been a good way to earn spendable money with which to purchase items from local or distant suppliers. If, on the other hand, the hypothesis is false, then by the 1820s there was a large amount of under-utilized pasture land in Worcester and the volume of timber had been greatly diminished to clear land for unclear purpose. * * * * * |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Data from Lincoln’s transcription of state assessors’ reports (p.262):

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||